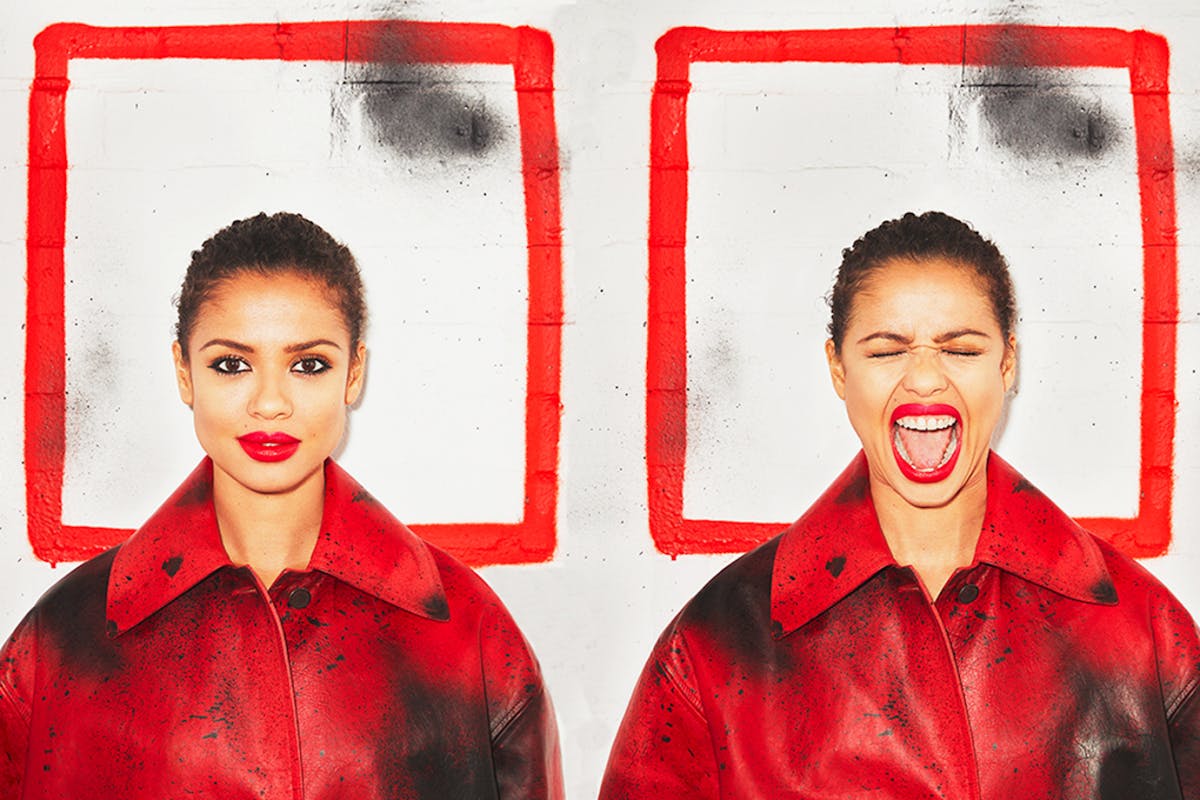

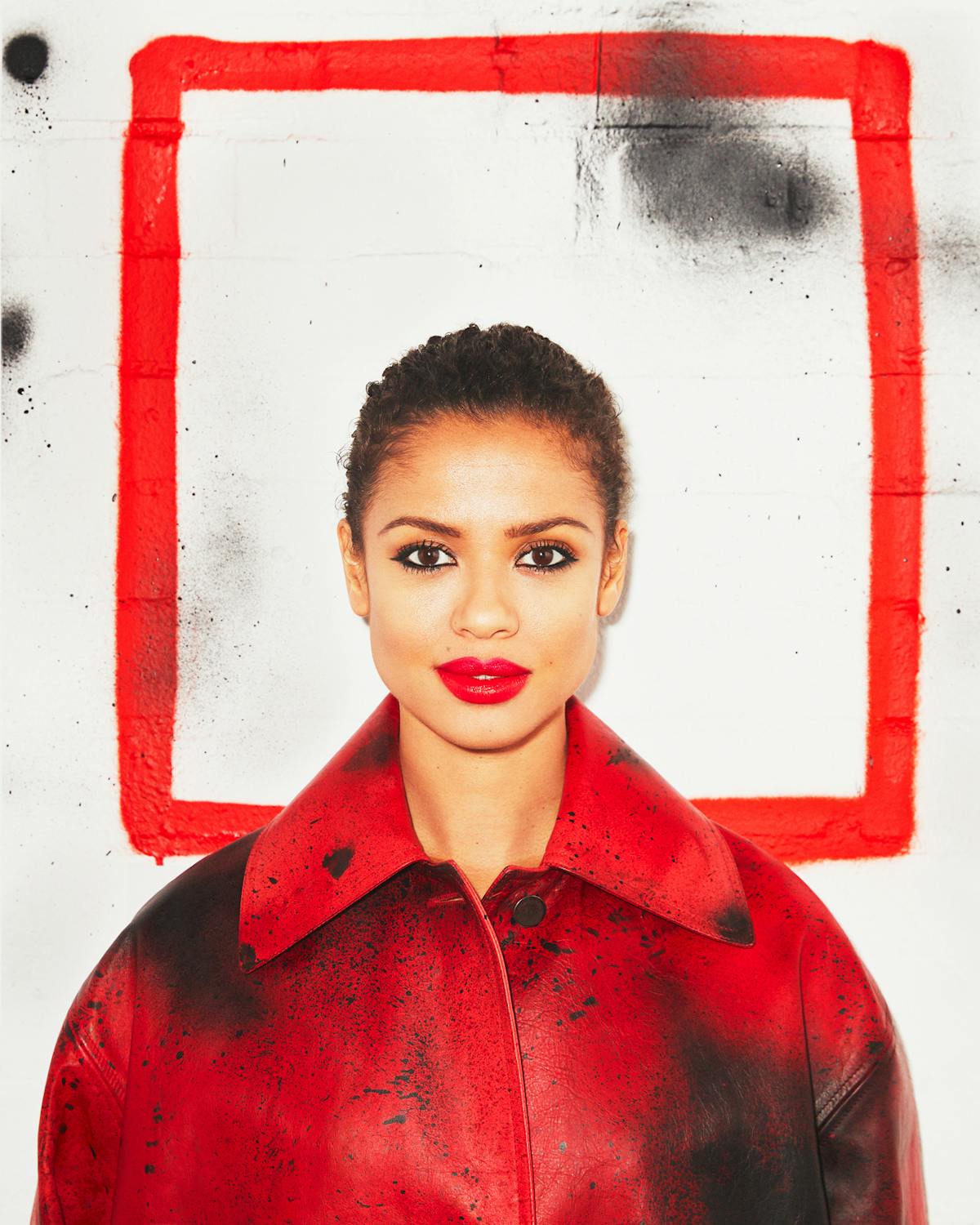

Already one of Britain’s most promising actors, Gugu Mbatha-Raw is now joining the A-list and working with the likes of Oprah, Mindy Kaling and Reese Witherspoon

Late last year, Gugu Mbatha-Raw received a phone call from her mother. A letter had arrived at the family home in Witney, Oxfordshire. It wasn’t in just any old envelope; this bore a seal, and the words “Her Majesty’s Service”. Mbatha-Raw giggled down the line from Los Angeles. “Mother!’ she said. “It’s the damehood!”

The truth’s not so far removed: when we meet for lunch in London in January, Mbatha-Raw is fresh from a trip to Buckingham Palace to collect an MBE. “It was incredible,” she says sounding wistful, slightly in awe. “A chamber orchestra performed, sun streamed through the windows. Afterwards there was champagne and photos. It felt like a very posh graduation.” Still, if you think she’s wide-eyed about it, you should see her parents: “I think they’re more impressed than they would be if I won an Oscar.”

Awards season and its role in celebrating, or at least promoting, issues of diversity and equality is everywhere when we speak. “As much as people may be critical of those zeitgeisty moments, they have changed awareness,” she says. “Producers and casting directors have had to interrogate their choices, and it’s the same with the women’s movement: people are now calling out who’s not in the room, who’s not represented.”

In many ways, she observes, we’re repurposing awards ceremonies now. As protests? “Yeah, and that’s a good thing. I think we should be using them as ways to have discussions, rather than just treating them as shiny ego boosts for the industry. Because at some point, you have to ask: ‘What are these pats on the back for?’”

I wonder if Mbatha-Raw has ever felt a pressure to be a spokesperson. There aren’t many bi-racial women flying a flag for Britain in Hollywood. Is there a duty to represent, alongside the work? She thinks for a moment. “Well, I think it’s got to be authentic to your personality,” she points out. “So I don’t think you have to be a mascot for a cause, no. Personally, I think quite carefully about the choices I make, in terms of the work, and there’s a power in that choice. You know, sometimes I think choices speak for themselves.”Mbatha-Raw has known Oprah for a while now. “We met when I was promoting [the 2013 film] Belle, and we’ve stayed in touch,” she says. “We email, and I see her from time to time.” So what does she think of Oprah as the next president? “Oh, she’s so influential and wise,” she says as if it’s blindingly obvious, “I think she’d be amazing. To take a moment like that [an awards acceptance speech] and really use it as your platform… to have that power and confidence. I find that so inspiring.”

Belle was the true story of a bi-racial aristocrat raised by a white family in Georgian Britain. Oprah offered her assistance in marketing it in the US. “The next thing we knew she’d invited the cast to lunch in her garden in Santa Barbara, and when we got there, she’d invited a film crew. So she basically made a moment for the film in America.”

Mbatha-Raw had grown up watching Colin Firth’s Pride and Prejudice on TV with her mum in an era of Jane Austen adaptations, “but brown people don’t figure in those stories or they’re usually brutalised, subservient,” she says. “You’re basically a servant.”

Belle was different, giving a voice to a tale that rarely figures in the history books. “It had this very pioneering spirit,” she says. “In films, books, people generally go with what we know. The same stories get told. But this wasn’t from a novel.” She makes the point so elegantly, and with such passion. As the film’s director Amma Asante reveals: “Belle was a role Gugu chased down for eight years. A lot of actresses wanted that role, but she kept on it, all through development. So I think for her, there was definitely much more to the film than just giving a great performance.”

Mbatha-Raw has already worked with three major black female directors: Asante (who made 2017’s A United Kingdom); Love and Basketball auteur Gina Prince-Bythewood, whom Mbatha-Raw worked with on critically acclaimed hip-hop drama Beyond the Lights (“The moment she auditioned, she was creating the film before my eyes,” Prince-Bythewood remembers), and now Ava DuVernay.

But her life still has its share of “starry moments”, which is how she describes appearing on the 2016 Hollywood cover of Vanity Fair alongside Helen Mirren and Jennifer Lawrence. This month she stars on the cover of British Vogue. It’s also part of the job to attend the red carpet events and glitzy premieres. Talking of which, doesn’t rumour have it that Prince played at a certain after-party?

“Ah,” she says, looking part surprised, part embarrassed. “Yes, that was for Belle. But I’d actually known him for a few years before.” How so? “He was accepting a lifetime achievement award at a ceremony that I attended, and he invited me and a friend to one of his house parties.” She chuckles: “I know, it’s crazy.” Then she waves a hand, eyes suddenly looking glassy. “Sorry,” she says. “He became a really good friend.” To this day, she still has the T-shirt he made her for Belle’s premiere. “He was really supportive of emerging artists, so he came and DJ’d – he said he wanted to create an ‘energy vortex’,” she laughs. “He was wearing a T-shirt with Belle printed on the front. And then he gave one to me.” She waves the hand again. “When he died, it was a shock. I found out about it on my birthday.”

Born in 1983, Mbatha-Raw would have been just a year old when Prince picked up his Academy Award for Purple Rain. At this peak in his career, her mother, a white British nurse, and father, a black South African doctor, would more likely have been fans. Actually, Mbatha-Raw says, she was raised mainly on jazz; her parents separated when she was one and she recalls listening to Ella Fitzgerald and Nina Simone in the car as a little girl, on the way to ballet with her mum. As an only child, every weekday evening was filled with after-school clubs. “My mum was an only child, too, so we didn’t have a big family. I was one of those kids who was signed up to everything.” By the time she was eight, she’d already requested to attend the Sylvia Young Theatre School in London – a decision that was probably inspired by Billie Piper. “She went there and she was a huge pop star. But there was also this show on TV called The Biz. It was Paul Nicholls in his really cute teenage days, and it was about a stage school. I absolutely loved it.”

Looking back, it was probably a good thing that her mum couldn’t afford Sylvia Young’s, she says. “When I got to Rada at 18, I’d had a normal upbringing – I wasn’t one of those actors who had already been worn down for 10 years when they started working.” She also thinks her mixed heritage has given her a useful perspective: “When one of your parents is from somewhere else, I think you look beyond your hometown. My name is rooted to a different culture [her full name is Guguletu, which means “our pride” in Zulu], and when you’re tethered to another place you look outwardly at the world.” For the first few days of her life, she was actually called Sophie. “Then my dad changed his mind,” she laughs. “Now I have a name that everyone asks me how to pronounce five times and can never spell. But do you know what? You apologise for it or you own it. So, I choose to own it.” In Hollywood it works, she says; you never get confused with anybody else.

She has been living there for years now, although she admits she can only manage around six weeks at a time before getting itchy feet. Recently she started work on the drama Motherless Brooklyn (with Bruce Willis and Alec Baldwin), making it the second time in six months that she’s filmed in New York. You get the impression that might suit her better. But she’s constantly moving, the list of upcoming projects growing. Later in the year she’ll work with Gina Prince-Bythewood again, on an adaptation of Roxane Gay’s novel, An Untamed State.

The project she talks about most is Farming, a low-budget British independent based on Nigerian-British writer Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje’s experience of being fostered by a white working-class family in Essex, not due for release until later this year. Set in the 1980s, it examines the effect of thousands of Nigerian children being farmed out to private carers in the UK, many of them never registered with social services or reunited with their parents.

For Mbatha-Raw, it’s an important story to tell. “I guess it’s another chapter in British history that hasn’t really been revealed,” she says. It’s these kind of nameless stories that are becoming key to her work: “At the beginning of your career, I think it’s about having the luxury of being able to work. Then, maybe the why becomes more important. The more you do, the more you question why. You start to ask if you should be contributing something, rather than just entertaining.” She smiles, warm and amiable, but I can’t help noticing there’s ferocity there. “Now, when I’m thinking about investing my time in a project, there’s always that question: ‘How will this be worth it?’”

A Wrinkle in Time is out on 23 March

Set design by Alun Davies; hair by Earl Simms at Caren using Hair by Sam McKnight; make-up by Camilla Hewitt at Frank Agency using MAC Cosmetics; photographer’s assistants Michael Furlonger and John Munro; fashion assistant Bemi Shaw; set assistant Kaushal Odedra